general commentary on psychology and psychotherapy, and other stuff too from time to time

Docsplainin' -- it's what I do

Docsplainin'--it's what I do.

After all, I'm a doc, aren't I?

After all, I'm a doc, aren't I?

Pages

Monday, July 15, 2013

Poor Trayvon

Labels:

George Zimmerman,

gun violence,

National Rifle Association,

stand your ground,

Trayvon Martin

Location: Woodstock, GA

Woodstock, GA, USA

Sunday, June 23, 2013

On Humility, and the Limits of Formal Education, or More on Arrogance

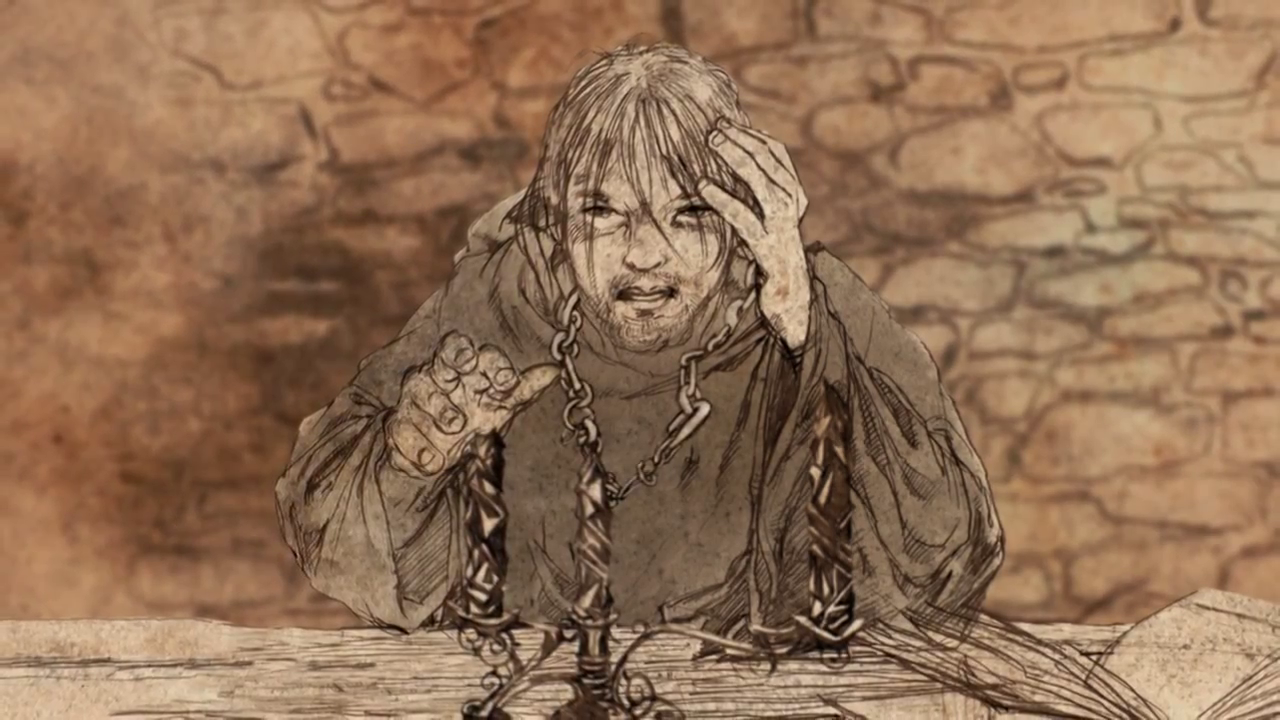

"The night before an acolyte says his vows, he must stand a vigil in the vault. No lantern is permitted him, no torch, no lamp, no taper . . . only a candle of obsidian. He must spend the night in darkness, unless he can light that candle. Some will try. The foolish and the stubborn, those who have made a study of these so-called higher mysteries. Often they cut their fingers, for the ridges on the candles are said to be as sharp as razors. Then, with bloody hands, they must wait upon the dawn, brooding on their failure. Wiser men simply go to sleep, or spend their night in prayer, but every year there are always a few who must try."

". . . what's the use of a candle that casts no light?"

That stopped me in my tracks. I read it again. And then once more. And I wished that (or something like it, since we have neither dragons nor dragon glass in 21st-century America) had been our last lesson, perhaps the night before our hooding ceremony, since we don't don chains like the maesters of Westeros."It is a lesson," Armen said, "the last lesson we must learn before we don our

maestcr's chains. The glass candle is meant to represent truth and learning,

rare and beautiful and fragile things. It is made in the shape of a candle to

remind us that a maester must cast light wherever he serves, and it is sharp to

remind us that knowledge can be dangerous. Wise men may grow arrogant in their wisdom, but a maester must alwavs remain humble. The glass candle reminds us of that as well. Even after he has said his vow and donned his chain and gone forth to serve, a maester will think back on the darkness of his vigil and remember how nothing that he did could make the candle burn. . . for even with knowledge, some things are not possible."

How I wish they'd taught us how to simply sit with the dark.

I have been a therapist for 33 years, and in that time I have seen many who have grown arrogant--in their knowledge, if not their wisdom. I have seen a few use their knowledge in dangerous ways. And I have seen not a few who think that because they have the terminal degree, they must know everything. I have known psychologists trained in the scientist/practitioner tradition who abandoned all pretense at critical thinking the evening of the day they defended their dissertations. I have known psychologists who thought they had nothing else to learn and shut their minds to new ideas and new data. And I've met very few who didn't hold themselves above the less-educated. The whole profession has come to think of itself as wholly superior to masters-level practitioners, and spends a lot of time dissing them and expending energy defending turf from them that might be put to better use elsewhere. But that is another rant for another day.

Worse, and there is another rant coming on this one in a future post, psychology has come to believe that they have the power to change people. Therapy has become and "intervention" to be "delivered" as if to a retail consumer and its success is to be measured in "behavioral outcomes".

Our clients believe this, too, and will say to us, "What do we do about it?" or, "I am ready to be fixed, now." And when we can't, they ask us, "What is the use of a candle that casts no light?" So we are seduced into trying, only to bloody our fingers once more.

As the next passage in the Prologue to A Feast for Crows makes plain, the obsidian candle can give off light -- but that's not under our control.

"I know what I saw. The light was queer and bright, much brighter than any

beeswax or tallow- candle. It cast strange shadows and the flame never

flickered, not even when a draft blew through the open door behind me."

Armen crossed his arms. "Obsidian does not burn."

"Dragonglass.'' Pate said. "The smallfolk call it dragonglass." Somehow that seemed important.

"They do," mused Alleras, the Sphinx, "and if there are dragons in the world

again . . ."

"Dragons and darker things,'' said Leo.The dragonglass candle is in this sense a metaphor for healing, and gives another bit to the lesson Armen describes. Illness, unhappiness, neurosis--whatever you may wish to call it--is contained within us, and so is healing. There are things we may say or do, or not say or do in a session, things that grew out of our learning (not all of which is formal, by the way) that enter into a person in the same way that a maester's antidote enters the body to combat a poison, and we may contribute to a person's healing in that way. But in the same way that the antidote and the poison do battle inside the victim's body, with the body itself as one of the combatants, so, too, is psychological healing an inside job. We have very little power compared to what resides in you.

And powers far greater than either of us may determine whether that candle burns.

Monday, June 17, 2013

From the In Box

People can get better over time, either because 'time heals all wounds,' or due to other things occurring in their lives during the course of the study. The authors performed a statistical test for this, but still, a control group would have helped to tease out how much improvement is due to the program itself, and how much due just to life going on. And since some study participants were receiving other treatments at the same time, there's no telling exactly what improvements are due exclusively to REACH. It is well known that when people invest a lot of time and energy in something, there's a psychological bias towards finding it worthwhile. This is true for researchers and participants, and is bound, in this kind of study, to influence the reporting and interpreting of results.

Of course, there's no reason to believe that it wouldn't work for a wider range of folk, since groups in general have been studied for over half a century now and the results are consistent. It works for nearly everybody, for nearly every problem. It's just that with this study, the authors could not claim with any certainty that this particular protocol would work for other than adult, straight, white males of a certain age.

The authors note that in a study of this sort, while you can say you're pretty sure the program helps, it's hard to say exactly what components of the program are most -- or least -- effective. That makes it a bit of a crapshoot whether you can replicate the results elsewhere. What if, for example, one of the only four psychologists running the study is just especially talented, and no matter what she did, her people would get better? On the other hand, if the standard curative factors of all effective groups were in operation here, you could do REACH or any other variation of multifamily group and get the same results anywhere. This is why we like to see multi-center studies, or studies replicated elsewhere producing similar results. However, when you are running only 4-6 vets and their families through at a time, and the whole process takes nine months, as this one does, we'd be waiting a minimum of four more years for the next study -- and that's not counting the time to organize and fund a study, write it up, and get it into print! So I think you will see a lot of psychologists running with this one, and soon.

Fischer, E. P., Sherman, M. D., Han, X., & Owen, R. R. (2013). Outcomes of

participation in the REACH multifamily group program for veterans with PTSD and

their families. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice (44), 127-134.

Labels:

Posttraumatic stress disorder,

PTSD,

veterans,

vets

Monday, June 10, 2013

Think With Your Whole Body

Labels:

Meditation,

Mind,

Mindfulness,

stress,

Thought,

unified experience

Location: Woodstock, GA

Woodstock, GA, USA

Monday, May 6, 2013

International No Diet Day

Labels:

Body image,

feminism,

Health,

International No Diet Day,

Weight loss

Monday, April 1, 2013

Fat and your health

Labels:

Health,

Mindfulness,

Weight loss

Monday, March 25, 2013

On Best-Laid Plans

|

| English: Wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus) – (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

- The best laid schemes o' Mice an' Men,

Gang aft agley,

An' lea'e us nought but grief an' pain,

For promis'd joy!- Robert Burns, To a Mouse (Poem, November, 1785)

Scottish national poet (1759 - 1796)

Labels:

Plans

Location: Woodstock, GA

240 Creekstone Ridge, Woodstock, GA 30188, USA

Monday, March 18, 2013

Jimmy was right

| Jimmy Carter, former President of the United States. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

When he said that, I was young enough and naïve enough to expect that life should be fair, and so to be appalled at his comment. I loved Mr. Jimmy, but he broke my heart with that line." There are many things in life that are not fair."

-Jimmy Carter

In the intervening years, though, I have learned that life is, indeed, manifestly not fair and that when we persist in demanding that it should be (there's that word again), we set ourselves up for all sorts of misery.

I am not saying that we should not be willing to step up to address inequities when it is in our power to do so, only that in expecting the universe to operate along some sort of moral lines we add to the unhappiness that is already there. And sometimes we create the unhappiness.

I have come to believe that the sooner and more fully we can embrace the notion that we need to be able to accept life on life's terms in order to live happily, the better off we'll be. Harsh as it may sound, then, the real question becomes not "Why is this happening?" but "What do I intend to do about it?"

I suspect that when bad things happen, this is nobody's instant response. We all need a little time to wrap our heads around the new state of affairs, to take stock of things and begin to see where we stand now. But then we need to dust our butts off and get back up on that horse and ride it. Wise old horsemen would tell you that if you don't, the horse understands that he just got the better of you, and he'll remember that next time. In life, the message is the same except that you're the one getting it. Be sure the message you send your self is that you can cope, you can deal.

Location: Woodstock, GA

240 Creekstone Ridge, Woodstock, GA 30188, USA

Sunday, March 10, 2013

Words to Live By

| The Writing Life (Photo credit: Simply Bike) |

Labels:

Annie Dillard,

Writing Life

Location: Woodstock, GA

240 Creekstone Ridge, Woodstock, GA 30188, USA

Sunday, March 3, 2013

On Gratitude

| joy! (Photo credit: atomicity) |

I like that one, and I'm going to start prescribing it.

So hop to it. Unhappy? Get out your pen and paper!

Labels:

dog,

Donald Hebb,

gratitude,

Jon Kabat Zinn,

journal,

Mindfulness,

Pockets of Joy,

Pollyanna,

Thich Nhat Hanh,

Tiny Buddha,

Wood's rules

Sunday, February 24, 2013

Bullying

| Physical bullying at school, as depicted in the film Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

One very damaging aspect is the response of the people in charge. Bullying victims get doubly traumatized when teachers, administrators, and parents do nothing: This is experienced as a betrayal, an abandonment, or as further abuse--and sometimes, as all three. For example, a boy who was physically assaulted in front of a raft of teachers who did nothing reported it both the assault and the faculty's inaction to the principal. That worthy's response was that this would not have happened had the student not chosen to come out. In actual point of fact the boy had been outed by one of the bullies some months previously in a separate incident, and he had reported it at the time. So the victim gets the message that nobody cares, nobody's going to do anything, and it's his fault anyway. I suspect that, as studies of childhood sexual abuse have demonstrated, this kind of response on the part of adults is a risk factor for some of the more negative outcomes for the child.

Nor, as far as I can tell, are long-term effects limited to childhood experiences: I know one fellow, retired about four years now, who still has regular nightmares about workplace bullying he suffered. And I have worked with several veterans who count abuse by their superiors as among the worst experiences of their careers.

So am I surprised by the results of this study? Not hardly.

Labels:

abuse,

Anxiety,

Bullying,

Panic disorder

Sunday, February 17, 2013

If Everybody Did

Image by swanksalot via Flickr

Image by swanksalot via FlickrThe tax complainers seem to see taxes as some kind of terrible, unfair imposition, as if (a) they had nothing to do with electing the governments that assess them, and (b) they never use the services the taxes pay for. They complain about how the money is spent, without much actual awareness of where it really goes. About a fifth, for example, goes for Social Security and Medicare, both of which these folks will apply for the day they become eligible. They elect a government that takes us on military excursions overseas and then resent ponying up their share (almost another fifth of the national budget, not including veterans' benefits) every April. These same people send their kids to public schools and will not hesitate to call the police if their office is burgled, while resenting paying their fair share for these services via sales, property, and other local taxes.

A couple of years ago, the IRS released results of a survey in which about 84% of us said it was never ok to lie on your returns. From that, researchers assumed that about 16% of us cheat. I would bet that there's another few percentage points at least comprised of those who say one thing and do another. Add those together, and you get at least a $345 billion (yes, that's billion) shortfall in any given year. Approximately 3/4 of government borrowing goes to make up this shortfall, adding to the deficit every year. Is it any wonder that early in the wars we saw stories about soldiers' parents having to purchase and ship body armor out of their own pockets? Or that programs and services are being cut or terminated because of lack of funding?

Besides being illogical and selfish, it's unethical to lie on your tax return.

When I was a little girl, someone gave me a book on ethics called If everybody did. The gist of it was that there were some things one person could do once that had small(ish) consequences, but if everybody did it, well, then. . .

Kant for short people

I've been thinking a lot about that little book lately.

What if everybody who ever accepted cash for their work did not report it? What if everybody put their personal dry-cleaning bills, club memberships, and even church pledges down as business expenses? What if everybody claimed everything they bought at the drugstore, from magazines to shaving cream, as medical expenses in order to get the itemized deduction? And before you ask, yes, I've personally known people who've done every one of these things. Where do you think the the money would come from to treat injured veterans? to pay for your Daddy's nursing home? to upgrade the armor on that HUMVEE your cousin's riding around Afghanistan in?

When you cheat on your taxes, you are not cheating the IRS. You are, in effect, cheating your fellow citizens. Your coworkers. Your neighbors. Your children. Your parents.

The irony is that none of these people think of themselves as illogical, selfish, and unethical, or as liars, cheats, or criminals, despite the fact that they are every one of these things.

The whole system is based on self-reporting, on trust. If everybody lied and cheated, it would collapse. If everybody dragged their feet like I've been doing, we'd have to borrow even more every year to keep the government running (10% of the budget every year goes to interest payments as it is). The IRS would have to audit everybody, or maybe they would require all our patients, customers, clients, etc. to start issuing us 1099s at the end of the year. Or maybe we'd just go back to the system of old, when the government just showed up at your front door and took what it needed at the point of a spear. How would you like that?

So you just think about that the next time you are tempted, as a former colleague liked to put it, to "round things off at the corners". I know I'll be thinking about it this spring when the temptation to procrastinate arises.

What if everybody did?

Related articles by Zemanta

- Why we cheat on our taxes (msnbc.msn.com)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)